Stagflation Worries Grow as Inflation Rises and Delta Variant Explodes

Stagflation Worries Grow as Inflation Rises and Delta Variant Explodes

With each passing month, it becomes more difficult to dismiss inflation signs as “transitory.”

Inflation first grabbed our attention this year back in April, when the year-over-year Consumer Price Index (CPI) jumped 4.2% – at that time the biggest increase since September 2008. Federal Reserve officials and economists were expecting to see a big move that month, but the number turned out to be larger than practically anyone had expected.

Then came May’s CPI: 5%. That was followed by another increase in June of 5.4% as well as a repeat of that figure again in July. If inflation indeed is going to be a passing phase, it certainly seems to be taking its time about it.

And that’s just the point, some say. It isn’t going to be a temporary blip on America’s economic radar screen but a persistent feature with which we all will have to deal.

For his part, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell isn’t abandoning his narrative of no rate hikes. Powell has said all along that while he remains concerned about rising prices, he’s even more concerned about ensuring America’s economic recovery doesn’t stagnate. Powell’s principal focus is the nation’s jobless number. Unemployment has struggled since the beginning of 2021 to drop appreciably lower than 6%. And while it did sink in July to 5.4% it remains more than 50% higher than pre-pandemic levels.

Troubling signals about the nation’s economic output in the near-term future include the resurgence of the COVID crisis in the form of the highly infectious delta variant.

After all of the help that has been thrown at the economy in the form of ultra-easy-money policy and unrestrained government spending, the persistence of relatively high unemployment is a concern – and it’s not the only one. Troubling signals about the nation’s economic output in the near-term future include the resurgence of the COVID crisis in the form of the highly infectious delta variant as well as worrying consumer sentiment data registered over the last two months. And the prospect of an anemic economy living alongside inflation gives rise to fears that a stagflationary environment soon could be upon us.

Stagflation is a when there’s inflation but no economic growth.

Simply put, stagflation is a condition wherein there’s inflation without economic growth. Some readers might remember stagflation’s most memorable period in U.S. history, the 1970s. From 1970 to 1980, inflation frequently reached double-digit highs while averaging nearly 8% for the entire period. At the same time, annual unemployment averaged 6.5%.

Those who do recall the economic upheaval of the decade that came to be known as the “Great Inflation” might remember the strong performance put in by both gold and silver during those years.

The demonstrated strength of precious metals during America’s most notorious period of stagflation is something worth noting, in my opinion. And while there’s no way to know if metals again will thrive during another period of stagflation, the potential of gold and silver to strengthen in such an environment may be of assistance to some retirement savers looking for ways to navigate the uncertain conditions that could lay ahead.

Lachman: COVID Delta Variant Could Be Stagflation Trigger

To be clear, concerns about stagflation are not idle ramblings from bored alt-financial personalities looking for a way to increase a following. Among those genuinely worried stagflation may be upon us shortly is economist Desmond Lachman, former deputy director of the International Monetary Fund. In Lachman’s view, there’s a “real risk” we’ll see a return to 1970s-style stagflation due to monetary and fiscal policies that effectively invite inflation as well as an unsettled employment picture that could darken in the shadow of the COVID delta variant.

As for monetary policy, there’s no debate the Federal Reserve has been highly accommodative in its posture since the pandemic blew up, something Lachman specifically acknowledges. Lachman notes that rates have no choice but to remain low and the money supply bloated as a direct result of the $120-billion-per-month pace at which the central bank is making asset purchases. And Lachman mentions the application of policy on the fiscal side has been similarly unrestrained.

The economist points out the December 2020 COVID stimulus package and American Rescue Plan together will infuse what amounts to a record sum for single-year peacetime budget stimulus, equivalent to 13% of gross domestic product (GDP).

Together, Lachman says, those factors are poised to help keep inflation well-fertilized for the foreseeable future. But inflation by itself does not stagflation make. You need weak economic output, as well, and Lachman says ongoing unemployment struggles exacerbated by the dangerous COVID delta variant could prove a key player in the facilitation of that weakness. Additionally, Lachman says global supply chains could find themselves under intense pressure with the spread of delta in the same way they slowed to a crawl when COVID first gained critical mass.

The key risk that higher inflation will continue to be accompanied by high unemployment is that the delta variant might spread rapidly both at home and abroad,” Lachman explained. “Underlining this risk are the facts that this variant is much more infectious than the earlier COVID strains and that the vaccines seem to be less effective in protecting the vaccinated public against this particular strain than against the original strain.”

Sinking Consumer Confidence at Odds With Supposed Recovery

Declining consumer confidence is another sign the nation’s economic engine may be on the verge of slowing considerably. On that note, consumer confidence survey results from both July and August paint an ominous picture of Americans’ faith in their own personal economic viability as well as that of the nation as a whole.

Last month, results of the University of Michigan consumer confidence survey surprised observers when it was revealed consumer sentiment dropped from 85.5 in June to 80.8 in July – a five-month low at the time. The drop was a disquieting sign, particularly at a time when many have been under the impression the nation is in the midst of a highly energized recovery from the pandemic.

Survey director Richard Curtin explained the number this way: “Inflation has put added pressure on living standards, especially on lower and middle income households, and caused postponement of large discretionary purchases, especially among upper income households.” Of note was the particular lack of confidence in the outlook for vehicle and home purchases expressed by survey respondents. According to survey data, buying conditions for both vehicles and houses had sunk to their lowest levels since 1982.

But if the July number took some sentiment observers by surprise, they must have been downright stunned at the release of August’s figure – from 80.8 down to a paltry 70.2. As it turns out, that’s the lowest level to which consumer sentiment has sunk since December 2011. It’s even lower than the 71.8 reached in April 2020, the month pandemic-cued unemployment reached the highest level since the Great Depression.

“The slump in confidence risks a more pronounced slowing in economic growth in coming months should consumers rein in spending,” Bloomberg noted. “The recent deterioration in sentiment highlights how rising prices and concerns about the delta variant’s potential impact on the economy are weighing on Americans.”

As a leading indicator, consumer sentiment numbers could be more revealing as a measure of the economy’s near-term health than the unemployment number which itself is a lagging indicator. That consumer sentiment is as low as it is right now suggests Americans could be planning to pull back hard on the spending reins in the months to come. If that happens and the current inflationary backdrop remains intact, it’s reasonable to consider the possibility a stagflationary environment will ensue.

Gold and Silver Soared in Stagflationary ‘70s

You’ll remember I briefly mentioned the 1970s at the top of this piece as being America’s most noteworthy example of a stagflationary period. I also made reference to how especially well gold and silver thrived during the decade that Wharton professor Jeremy Siegel said served as “the greatest failure of American macroeconomic policy in the postwar period.”

But I didn’t say how well metals fared, so here it is. From January 1970 to January 1980, gold rose an astonishing 1,500% and silver rose an even more astonishing 2,100%. These are remarkable numbers, particularly when you consider the Dow Jones Industrial Average grew at a positively anemic 3% for the entire period.

So does this mean gold and silver again will soar against another stagflationary backdrop? No. But as retirement savers look for ways to effectively navigate their holdings during a period that could include – at a minimum – chronic inflation and perhaps even actual stagflation, the demonstrated capacity of metals to strengthen amid such conditions is worth noting in my view.

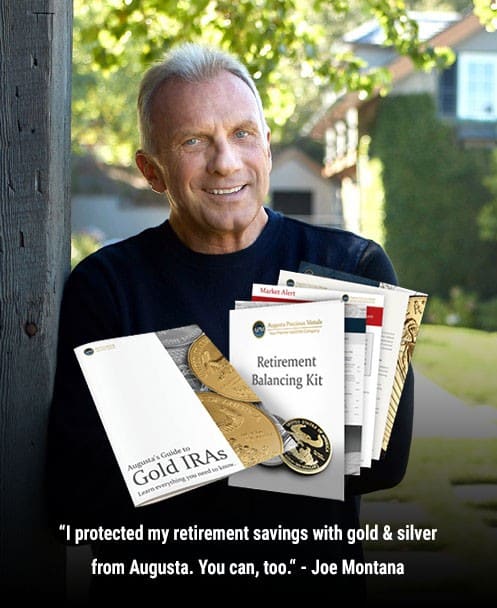

Interested in investing in Precious Metals?

Our top Gold & Silver IRA company that we recommend is Augusta Precious Metals.

Commitment to service sets Augusta apart from other companies. Every member of the Augusta team – from CEO to receptionist – is dedicated to helping retirement savers realize their dream of financial independence.

— One Percent Finance